[ 3 ]

Storytelling for Product Design

When Any Device, Used Anywhere and at Any Time, Is Your Starting Point

Back in 2011 Luke Wroblewski, an internationally recognized digital product leader tweeted: “So how do you do anything if everything, anybody, anywhere, & anytime are your use cases?” (@lukew, May 12, 2011). Though I didn’t have a clear answer, the topic of his tweet got me excited and kept my mind buzzing for the rest of the week. So much so, that I ended up submitting a proposal for a talk to a conference, which resulted in my first public speaking appearance and, as an extension of that, why you’re reading this book today.

A lot has happened since that day in 2011, and it’s even more fascinating to think about just how much our lives have changed since Apple released the first iPhone in 2007. Before then, we were limited to going online at work or at home, or to using a Wireless Application Protocol (WAP) browser—a web browser for mobile devices—on our phones. WAP was introduced in 1999, but what we experienced when browsing using WAP didn’t look anything like those websites we’d visit on our laptops or desktops (Figure 3-1).

By 2010 WAP had been replaced by more modern standards, and today most internet browsers of modern handsets fully support HTML, allowing us to experience the web the way it’s intended to look and work. This development has drastically changed things. In 2009, only 0.7% of all global web pages were served on a mobile phone. In 2018 that number rose to 52.2%.

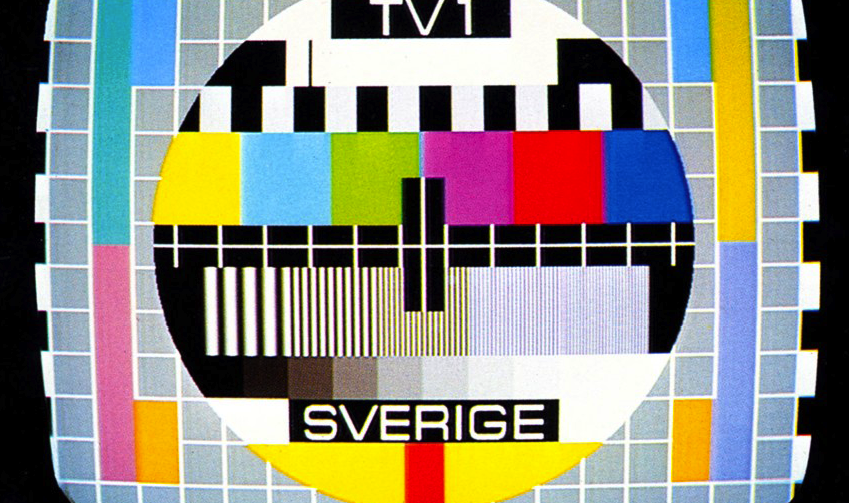

Figure 3-1

A page viewed in a WAP browser (source: Norbert Huffschmid, https://oreil.ly/NJW1Q)

We now go online absolutely everywhere and anywhere—the average smartphone user in the US checks their phone 150 times a day–from the first thing we do in the morning (including bringing our smartphone along to our morning visit to the little boys or girls room), to the last thing we do at night. Our addiction to smartphones has become such an issue that both Android and Apple have started releasing updates to help us monitor our usage and take a break from them and the apps we’ve installed.

Tasks like buying online, which we previously considered ludicrous to do on anything but a desktop or laptop, are now second nature to do on a smartphone. More than a fifth of online spending in the United Kingdom takes place on a commuter journey.1 Mobile-optimized websites that only a few years ago were still considered a nice option are now an across-the-board essential for business-to-consumer (B2C) and increasingly so for business-to-business (B2B), as more and more of the workforce is becoming flexible. In 2015, Google’s “Mobilegeddon” famously came into action, and websites that aren’t mobile friendly now get penalized in search rankings by the updated Google algorithm.

All of this has happened in just a few years. There’s no denying that the introduction of the iPhone and the other smartphones that followed have changed our world. This technology has changed how and where we go online, how we as human beings now communicate (or don’t, for that matter), the products and services we use, and how we go about our day-to-day lives with everything accessible at the tap of a button.

We’re now at a point where advances in AI, machine learning, Internet of Things (IoT), smart home devices, and VUIs are yet again changing everything. Though VR has yet to kick off as predicted, both VR and AR are making progress in the devices that are available and affordable as well as in the offerings for both. As for IoT, a growing number of devices are becoming connected via Bluetooth and the internet, from pregnancy tests, to fridges that scan food, to smart speakers like Amazon Echo and Google Home that enable us to control an increasing number of other devices and appliances in our homes with voice commands.

Soon pretty much everything will be connected in one way or another. The question Wroblewski asked is increasingly not a “What if,” but the new norm. Everything, anybody, anywhere, and anytime is what we’re dealing with, and we’re only at the beginning.

How Traditional Storytelling Is Changing

Technology and the other mediums that we’ve used have always shaped the way we tell and interact with stories as well as how people come across them. The latest developments in technology have contributed to the creation of new types of stories, from the introduction of photography, motion pictures, radio, TV, and later on internet with mobile as well as social media. These developments have not only influenced the creative ways that stories are brought to life, but also altered the structure of the stories themselves.

The immediate structure that comes to mind when we think of a story is the one we’re used to in books, film, and TV: a beginning, a middle, and an end, just as Aristotle defined it. But with recent developments in technology, new platforms and devices, and a growing on-demand culture, storytelling is changing. Next we’ll look closer at changes in eight areas, how they impact storytelling, and their relevance for product design.

The Shift to On-demand

One of the most obvious ways we experience stories is the increasing shift from linear TV to on-demand viewing. I remember as a child sitting in front of the TV with the test screen showing, which meant that there was nothing airing at that time (Figure 3-2).

Most TV programs would start around 3 p.m., and in total we had around five channels. Fast-forward a few years, and a more consistent broadcast schedule offered something to watch 24/7, albeit in some instances just the TV shopping channel. Still, we had to wait a week for the next episode of most shows. This wait was frustrating, but it built anticipation and made us look forward to certain shows, days, and times, in a way that most of the things we watch nowadays never come close to.

Today that wait for the next episode is almost nonexistent, and has been replaced in many cases by the wait for the next series. Netflix and other subscription video on demand (SVoD) services like Now TV, Amazon Prime Video, Hulu, and TVPlayer have changed the way we watch TV and films. We now watch when and where we want instead of at predefined broadcast times. And even more growth is expected to come in this area. In 2018, there were 283 million SVoD subscribers worldwide, and the number is expected to rise to 411 million by 2022.2

The shift to on-demand isn’t restricted to just TV and films. It also applies to novels and audio-based storytelling, as well as to games and applications. Back when I was a child, we went to the library in Lund, my hometown, every Saturday morning. We’d sit in the cafeteria and bring books along with us to read and used our library card to bring some of them home when we left. While this was a type of on-demand experience, and one that is still very possible, ebooks now account for about a quarter of global book sales,3 and digital audio book apps like Audible allow you to listen to almost any book in English if you subscribe and pay a monthly fee.

Figure 3-2

Swedish State Television screen used when nothing was on air

What this means for product design

The on-demand trend is an example of a general shift in consumer expectations. The rise of tap-of-a-button expectations increasingly means that users can get a growing number of products and services at the tap or click of a button. Users choose to view, read, listen, and interact on their terms, when it fits them, on the device and in the place that they prefer. We are no longer confined to watching the latest episode of a much-hyped TV series like Stranger Things in our living rooms; we can watch it anywhere with a good 3G, 4G, 5G, or WiFi signal, whether during the commute to work, in the airport, or sitting on a park bench.

We may have a particular device and viewing experience that we think is ideal for our users—for example, watching on the TV at home. But what users prefer is up to them, and “on my terms” is increasingly becoming a need rather than a “nice to have.” Where appropriate, we have to make sure that the content we’re creating can be experienced anywhere and anytime, and that goes for our products and services overall as well.

The Audience as Storytellers

Thanks to smartphones, we now consume more media than ever before, but how and what we consume has evolved. In 2017, we spent a billion hours on YouTube every single day. While the time we spend watching TV has been in a steady decline, YouTube is steadily on the rise and has surpassed both Netflix and Facebook video in terms of the number of hours we spend on the respective platform. As Cristos Goodrow, VP of engineering at YouTube said:

Around the world, people are spending a billion hours every day rewarding their curiosity, discovering great music, keeping up with the news, connecting with their favorite personalities, or catching up with the latest trend.4

This is a new type of storytelling, one that is less scripted, created by the masses rather than a specialist team, and is turned around in a very short period of time in comparison to other types of video content.

Every single hour, four hundred hours of content are uploaded to YouTube by what’s called YouTube creators. This creator trend isn’t just limited to YouTube, or to the more grown-up among us. At the end of 2018, YouTube revealed that its highest-earning creator was a seven-year-old boy named Ryan who reviews toys.5

As Lance Weiler, co-founder of Connected Sparks—a next-generation media and connected toy company—writes about his son and his friends, “The reality is, they are not watching TV but instead have become their own little media companies.”6 Weiler’s son and his friends are being inspired by creators that they watch, and then they themselves create their own Let’s Play (LP) videos, which document the play-through of a video game, usually involving commentary from the gamer. To some, these kinds of videos may seem pointless, and many would, if asked, have dismissed it as a terrible idea: “Who’d want to watch that?!” Turns out, a lot of people, to the extent that dedicated platforms have sprung up. The live-streaming video platform Twitch, for example, in 2019 boasted 3.7 million monthly broadcasters and active daily users who tune in to view both live and on-demand content on the platform.

What this means for product design

Increasingly, anyone can be a storyteller. From the updates, pictures, and captions we share on social media, to the videos we create, platforms like YouTube, Twitch, Snapchat, Facebook, and Instagram have made it easy for anyone to publish and reach an audience. And based on users’ needs, these platforms are constantly evolving.

In 2018, Instagram launched IGTV, a new app for watching long-form, vertical video content that can also be experienced within the Instagram app. In IGTV, your videos can be up to an hour long instead of being restricted to 15 seconds as Instagram Stories are, and the format is full-screen vertical video that automatically starts playing. And IGTV has channels just like TV, only the channels are the creators.

The new formats of storytelling combined with the audience as storytellers is putting changing requirements on brands, products, and services. While a piece of long-form video content previously would take months and a considerable budget to produce, brands and products and services owners increasingly need to be nimble and fast on their feet to keep up with how quickly their users and customers are producing content; and as an extension of that, how fast and frequently they expect others to be doing the same.

As we’ll cover in Chapter 4, “The Emotional Aspect of Product Design,” people are increasingly looking for ways to connect. That connection is usually not a polished piece of video when it comes to branded content, but a real story that moves the user—like the tweet series that Rosey Blair shared in July 2018. Blair’s tweet about a simple seat switch turned into a romantic story that was aired live as the events unfolded on the plane (Figure 3-3). The tweet has since been deleted, but at the time of this writing, over nine hundred thousand people had liked her tweet. Media across the globe, from the BBC to Buzzfeed, picked up and wrote about the story.

Figure 3-3

The first tweet in Rosey Blair’s tweet saga about #planbae and mystery woman Helen

The Audience as the Protagonist

One of the main characters in the preceding real-life saga was Euan Holden, otherwise referred to as #planebae by the public. While the woman of the story chose to remain anonymous, he went public. People from across the globe were checking in and following along the classic will-the-boy-get-the-girl kind of saga, and Holden found himself the focus of attention, with everyone wanting to know what would happen next.

One of the reasons film is said to make more of an impact on its audience than a play is that when watching a film, you can be more up close and personal with the characters than when sitting back in a theater watching a play. Though Euan didn’t deliberately place himself in the middle of the story, until he got involved, a possible reason for the attention this story got is how relatable it was. Many of us travel on some kind of public transport on a regular basis, and the “it-could-happen-to-anyone,” or even more so, “it-could-happen-to-me” aspect created a close connection to the story, plus, of course, the fact that we’re all drawn to a great love story.

The desire to experience things has been on the rise in the last few years. Interactive plays and experiences have sprung up, inviting the audience to be part of the story. One such example is Punchdrunk’s Sleep No More, which is an immersive and interactive version of Hamlet: the audience wears masks and experiences the play by wandering through the rooms of a hotel. Each room has actors playing out a scene, and the audience can engage with them and stay for however long, or short, they want. In some productions, the audience becomes the protagonist, and sometimes even antagonists and villains as well.

While not all of these types of interactive storytelling make the audience the main protagonist, they do make the audience one of the characters. This potential to offer something different and attract people has spread to other areas, too, like museums. Advances in technology are revolutionizing everything from how we experience art to how we learn about a subject, resulting in many museums seeing the best attendance they’ve ever had. The people who always tend to visit museums will visit either way, but for those who use museums as family time, or to fulfill a trend, the inclusion of tech like VR makes visiting a museum an easier choice.7 As an example, Figure 3-4 shows a screenshot from The Night Cafe: A VR Tribute to Van Gogh, in which the audience can explore the world of Vincent Van Gogh first hand, from his iconic sunflowers in 3D to walking around and seeing the chair he painted in his bedroom from every angle.

Figure 3-4

The Night Cafe: A VR Tribute to Van Gogh8

What this means for product design

People are increasingly looking for new ways to connect, and to experience things. With the development of AR and VR, actually placing the user in the middle of the experience has become a reality. Though these types of experiences, otherwise referred to as immersive storytelling, have so far had a fairly small audience, there is a growing appetite for it. In the AOL 2017 State of the Video industry study, 31% of Australian consumers expect to watch more movies in VR, and 22% already engage with AR at least once a week.9

From a creative and a data point of view, VR and AR are part of a fantastically exciting field. A staggering amount of data is available to gather from these types of experiences through heat maps that track eye movement, “gaze through rate” (the percent of people who trigger an event using their gaze), and motion-based interactivity. Creatively, AR and VR offer a new type of experience with no frame, and the ability to create a lot of empathy and participation from the audience. And it has the ability to do immense good for the user too.

While not all products and services lend themselves, or should, to offering immersive experiences in the form of 360° VR or AR, we should still aim to make the user the main protagonist of the products and services that we design. The way we talked about our products and services back in the early days of “digital” was much more about us than our users and customers. Today, the focus of the most effective and successful products, services, and marketing campaigns is on the users and customers rather than the company or the brand. We’ve come to realize, not the least through data, that what users and (prospective) customers respond to the most is messaging that’s indirectly about them, and we do this by creating pictures in their heads about what using the product or service will enable them to do.

Participative and Interactive Storytelling

In interactive experiences like Punchdrunk’s Sleep No More, audiences are invited to participate and explore the space individually, hereby influencing what to watch and where to go. This is in line with how audiences in general aren’t shying away from wanting to have a say. In a Latitude study about what audiences want, 79% suggested wanting interactions that would allow them to influence the characters’ decisions and thereby the way the story developed, or for them to become characters themselves. The ability to influence the story is something that became popular with the choose-your-own-adventure (CYOA) genre for books back in the 1980s and 1990s. However, for film and TV, though there have been a couple of examples, it has not taken off. At least not yet.

Over the last few years, movies have been losing potential viewers to games, a problem that is likely to only increase in the years to come.10 Young audiences in particular are less keen on being passive viewers, and broadcasters are looking for better ways to engage viewers and create loyalty.11 One example is Mosaic, a murder mystery by Steven Soderbergh that was released as an iOS/Android app in 2017 and then in 2018 as a TV series. The app worked like an interactive movie where the user could choose which viewpoint to see the movie: as well as explore different facets of it. The TV series didn’t have any interactivity and was slightly shorter than what could be experienced in the app. Both the app and the TV series got mixed reviews, some praising it and some saying that the storyline got a bit confusing and you risked missing crucial bits in the plot.

What this means for product design

When audiences are involved in helping shape what happens next through co-creation, or even if they’re only choosing the way in which they experience the different parts of the product or service, it places bigger emphasis on creating a flexible and adaptable product experience—one that can be viewed or engaged with in whichever order the user chooses. A few years ago, I was watching an interview on BBC Breakfast with part of the cast of the British “Nordic” Noir TV show Marcella. During the interview, the cast told how they didn’t know what would happen in the next episode until they got the script for it. In real co-creation, this will always be the case for the people involved. Though co-creation can often shorten the production process, in instances like the AXE Anarchy campaign, it can also take longer. In this case the men’s fragrance company created a campaign in which users created a narrative out of their own choices, and the agency Razorfish then transformed into a comic book that engaged thousands.12

Data-driven Storytelling

Beyond participative and interactive storytelling, we’re increasingly seeing examples of data influencing what we see, as well as when and how we see it. One of the main examples of data driving what we watch can be found in the way Netflix uses data to, among other things, identify which shows to commission and then what the ideal combination of factors (actor, duration of the film, setting, etc.), will be before making a decision about the same.

One of the most talked about examples here is how House of Cards came to be. The team at Netflix analyzed the organic viewing behaviors of its users to understand what they were already paying the most attention to. Netflix identified that the people who watched the original BBC version of the series also watched movies that were directed by David Fincher and starred Kevin Spacey. This led to the new version of House of Cards starring Spacey and directed by Fincher.13

In a TED talk analyzing the then difference between Amazon’s and Netflix’s approach to data for making hit TV shows, data scientist Dr. Sebastian Wernicke talks of how Amazon looked at data in relation to a controlled subset of pilot episodes when it commissioned Alpha House, whereas Netflix analyzed the consumption across its entire platform when it came to House of Cards. What Wernicke identified over the course of his career as a data scientist is that data in itself is good only for dissecting a problem and for understanding the multivariables of the same. Additionally, he’s identified that to be successful and to apply the data and the insight in the right way, you need to combine industry expertise in the process. With House of Cards, the data didn’t specifically direct Netflix to license it, but it pointed the company in the right direction.14

What this means for product design

Just as Netflix did when it came to investing in and making decisions around House of Cards, when it comes to the products and services we work on and the decisions that guide what we do and don’t do, we have to look at data holistically, across the whole system, rather than fall down the trap of looking at just reactionary data in relation to a subset of what we’re testing. As Wernicke pointed out, we should also include industry expertise to help get to the right insight and ensure we make the right strategic decisions.

With the right insight and the right decision making around it, data has the potential to improve both the bottom line for the business and the experience for users by providing more of what the user is interested in and less of what they’d prefer not to see.

New Storytelling Formats

Lance Weiler, co-founder of Connected Sparks, describes how storytelling has changed in the digital age, that while motivations are at the heart of storytelling, our desire to commercialize storytelling is what has driven and given birth to new storytelling formats. When theater owners realized that their audiences looked at the length of the films as a measure of quality, short form was replaced with longer-form film. Feature films also meant that a higher price could be charged, and various distribution channels were established to make the most of the opportunity. However, as Alfred Hitchcock famously said later, “The length of a film should be directly related to the endurance of the human bladder,” and theaters went from previously having intermittent breaks to account for the audience’s physical needs to the more bladder-friendly running times that we have today.15

The commercialization drive and the advances in technology have also evolved the types of stories that we are engaging with. When Snapchat launched in 2011, it was the first to introduce disappearing pictures. Brands that had previously created horizontal and mainly long-form video content for their users and customers had to adapt and create vertical video and image-based content as well as adapt to the original 10-second restriction that Snapchat had for snaps. After Instagram followed in Snapchat’s footsteps with 15-second videos called “Stories” that also disappeared after 24 hours, both platforms adapted—Snapchat allowed users to save snaps as “Memories,” which Instagram called “Highlights.” Snapchat’s original 10-second limitation was also removed in 2017 in favor of sending snaps with unlimited viewing time.

What this means for product design

The rise of new platforms like Snapchat and the accompanying new formats impact businesses as, for example, print and TV budgets are being replaced by Snapchat and Instagram stories. Rather than just push purchases, these stories often give a behind-the-scenes look at the brand in question for the purpose of entertainment and connecting with the brand, and that’s increasingly what audiences are after.

By listening to what our users want, and those who create content for our products and services, we are able to follow along with and adapt to their changing wishes and needs, and to the new formats out there. But, as we’ll cover next, we also have an opportunity to push how we tell our stories. Creativity, technology, and the idea of the kind of story we’d love to tell are leading the way.

Transmedia Storytelling

As the previous examples of Snapchat and Instagram show, new formats for storytelling are closely linked to new platforms and players in the technology market. A form of storytelling that is increasingly being talked about in relation to (new) platforms is transmedia storytelling.

Transmedia storytelling is a technique that is used to tell stories across multiple platforms—TV, radio, novels, games, online social media, a website, or any platform where a story can be told.16 In transmedia storytelling, the story itself unfolds in different ways; the audience can not only enter the story through different entry points, but also continue exploring the story through the various platforms. The idea behind it is that by telling (part of) the story across different platforms, you can give the audience more of what they want but also make sure you reach audiences that you may not otherwise have attracted (e.g., through social media).

A show that’s been widely acclaimed for its approach to transmedia storytelling, as well as the storyline and subjects it covered, is the Norwegian show Skam (“Shame” in English), which follows a group of teenagers at the Hartvig Nissen School in Oslo. Skam is a fairly traditionally produced TV show with four seasons, each one following a different central character. What makes it unique is how it aired in real time and evolved, transmedia, between each episode.

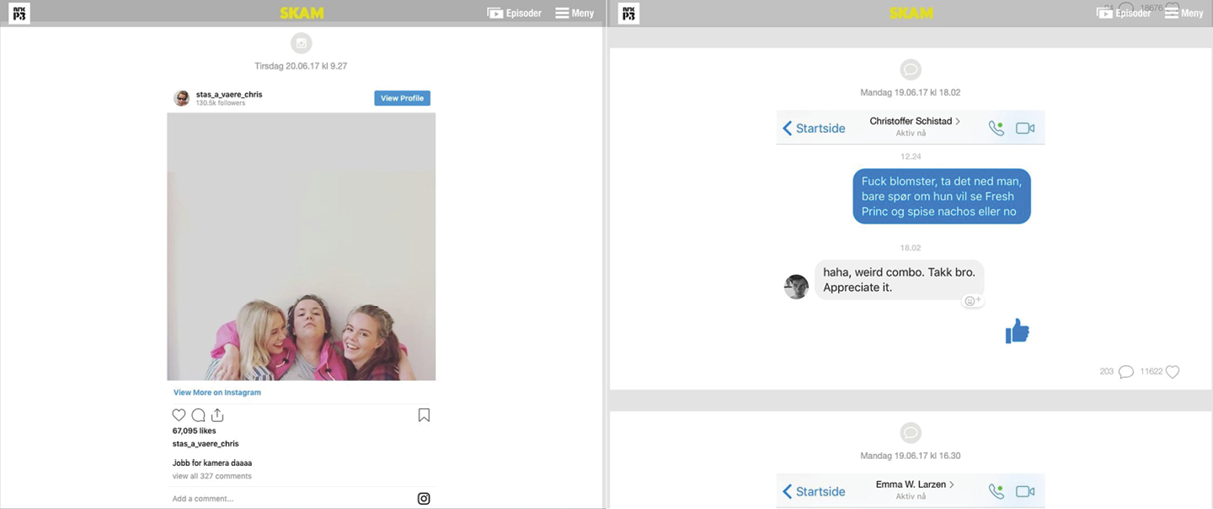

At the start of each week a clip, conversation, or social media post was published on the Skam website at the same time that it would happen in the world of the characters; for example, if two of the characters, Eva and Noora, are discussing something on Tuesday morning at 9:30 a.m., then the clip would go up on Tuesday morning at 9:30 a.m. New material was added daily before all of it was put together into an episode that aired on Friday each week. Between the updates, the audience could also read text messages that the characters would send each other via the Skam website and follow their Instagram accounts, where the audience was also encouraged to interact with the characters (Figure 3-5).17

Figure 3-5

The Skam website (www.skam.p3.no) showing an Instagram update by one of the characters as well as text conversations

What this means for product design

Transmedia storytelling requires a deliberate choice to tell the respective story across platforms instead of just on a select few. When it comes to product design, we not only have to ensure that we tell our story across platforms, but also need to consider how and what we deliver in that context. Our users are on multiple platforms, and, as we’ll be covering later, we can’t always control how they start their journey with us. When it comes to transmedia storytelling, 82% want complementary apps instead of duplicated content, and this is something we have to keep in mind for products and service experiences too.18 While the general guideline is that the same website content should be present on the mobile view as on a desktop or tablet, opportunities exist to adapt to the specific platform, and also, where appropriate, to provide an additional offering in, for example, an app.

Expanded Versus Adopted Universe

Closely linked to transmedia storytelling is the concept of the expanded versus adopted universe. The expanded universe includes any official content that essentially expands the existing fictional universe beyond what we already know; for example, The Walking Dead video game that’s part of the franchise and that introduces new characters and storylines. The adopted universe, on the other hand, can have either official or unofficial content that reimagines or reinterprets parts of the fictional universe, but what happens here doesn’t affect the original fictional world. The Walking Dead TV show is an example of an adapted universe, as what happens there doesn’t impact the original comics.

Before the internet, some quite obvious factors restricted how much the expanded or adopted universe of a fictional world could grow. These restrictions were physical in terms of awareness and accessibility—a book or comic book may not exist in your location, for instance. The internet changed that, and with social media and a growing on-demand culture, both expanded and adopted universe content is readily available, and it’s relatively easy to reach a large audience base.

Creators, fans, and investors benefit from the expanded and adopted universe of content. As with transmedia storytelling, this expansion provides an opportunity for us as brands, and for our products and services, in terms of what story we tell where. And it has the potential to turn what is otherwise a risk or threat into a new opportunity. This was the case with the role-playing game series original Mass Effect game, which was a huge success. In order to keep fans happy while waiting for the game’s sequel (which would take a long time to make), publisher EA Games began to release new downloadable content that expanded the stories and kept the audience engaged.

What this means for product design

The more we understand our users and what they are after, or would respond well to, the better positioned we are to fully cater to and look after them. We can then tell a story with our product or service that offers opportunities for expanded and adopted universe content as well as works across platforms and devices.

Next we’ll be looking in more detail at how the multidevice, multiplatform, multi-input method landscape that we now design for is evolving and the challenges these pose for us in product design, as well as why storytelling is so suitable to our field.

How the Landscape of Product Design Is Changing

The preceding sections cover a few ways in which traditional storytelling is changing and the way it’s impacting product design and marketing. Throughout history, traditional storytelling has influenced and driven innovation in technology and science. One example is Arthur Conan Doyle’s stories about Sherlock Holmes, which have had a lasting impact on the way crimes are solved. In the books, Sherlock Holmes is obsessed with protecting crime scenes from contamination. He is an avid user of chemistry, ballistics, bloodstains, and fingerprints to solve his crimes, all of which has helped shape what we now consider to be the foundation of forensic investigation.19

Of course, many fictional works have visions of the then future, now current day, that haven’t come to pass, yet. When Marty McFly warps from 1985 to 2015 with his girlfriend Jennifer and Dr. Emmet Brown, otherwise known as “Doc,” flying cars and hoverboards are widely used—neither of which are quite here yet. We also have a few years left until we’ll find out whether what we see in the movie Minority Report, which is set in 2054, will hold true.

However, as reported in Bloomberg: “It’s not hard to predict what the world will be like in 20 years. The hard thing is actually predicting or figuring out how to get there.”20 Be it those flying cars, intelligent humanoids like those in the film Ex Machina, or operating systems that we talk to and even fall in love with as in the movie Her, the one thing we know is that how and where we’ll be experiencing content and in what way we’ll interact with it is changing. In a not-so-distant future, we’ll look back at those pictures of people bending their heads down to look at their phones while walking on the pavement and smile saying, “Can you believe we actually did that?” just as we today chuckle sentimentally about how we used to use pens and pencils to rewind and fast-forward cassette tapes to save our Walkman’s battery.

The Future Starts Now

The thing about “the future,” however, is that it isn’t just about futuristic things like flying cars or talking humanoids. The future is very much about what’s happening, and starting to happen, right now—from the small to the big things. In its simplest form “the future” increasingly involves AI-powered products and services, multiple touch points, connected devices, apps and experiences, as well as a mixture of interfaces we touch, interfaces we talk and chat to, interfaces we cannot see, and interfaces that we are an actual part of through sensory data or AR and VR. We’ll increasingly be served with more tailored content and experiences based on preferences and what we’ve done or haven’t done. And we’ll come to expect more from technology. In fact, we already do. Google reported at the start of 2018 that people are increasingly using search as a personal advisor, with the qualifiers “me” and “I” in mobile searches up by 60% over the two previous years.21

With a growing number of moving parts (as we’ll look at in Chapter 7), making sure we know what story we’re telling with our products and services, along with why and how, is increasingly fundamental to making sure we deliver against users’ ever moving and more sophisticated expectations. It’s also critical in order to ensure that we not just keep up with, but also stand out from, the competition.

Next we’ll be looking at eight key areas, related to product design, the developments therein, and the challenges that we’re faced with in product design.

Free-flowing Content and Ubiquitous Experiences

For many of us, when we think about the future of interfaces, what we’ve seen in Minority Report comes to mind—interfaces that are controlled by gestures and that we can manipulate with ease. There are no restrictions on how we can move information around, or on what we can do. We simply “touch” the bits we want to interact with and manipulate them in any way we want, with the interface responding accordingly.

John Underkoffler, founder and chief scientist of Oblong, was part of the team that worked on the technology ideas for Minority Report. One of the principles behind what they developed was that the camera could go anywhere, and as a result, what they proposed had to be able to follow that and adapt. The technology concepts they worked on were originally based on setting Minority Report in 2080, but that was downgraded to 2044 and then at the very last minute upgraded again to 2054. Many of the ideas, like self-driving cars, didn’t make it into the movie, but the gestural interface, called g-speak, did, and it’s one of the things that Minority Report has become famous for. It’s also what became the foundation of what Oblong is working on today.

One of the underlying principles of how Underkoffler and his team see the future is that it shouldn’t stop at the boundaries of the device. If you’re near other pixels, and what you’re experiencing on one device can fit on that pixel, then what you experience should also be able to flow onto that other nearby pixel. This will require more systems and apps to talk to each other and for us to be able to map experiences in physical space rather than just a relative position on one screen.22

Minority Report isn’t the only example of where we’ve seen touch UIs and other NUIs be a key part of how people interact with technology. Though attempts have been made at larger touch interfaces, none have so far taken off, mainly because of cost.

In concept videos like materials science innovator Corning’s “A Day Made of Glass” vision for the future video series, we see what our future might look like when we have large surfaces in the kitchen, bathroom, and home office where we can be presented with information and interact with various apps. These range from watching the news and seeing the weather forecast while looking in the mirror and brushing our teeth, to following along with the recipe we’re cooking on the interactive kitchen counter.

What this means for product design

All of this is without a doubt a very exciting evolution of technology and user interfaces. But until it becomes a reality, the flow from one screen to another and having large interactive surfaces in our homes are but a good metaphor for, and reminder of, how we should think about product and service experiences overall. Our content will increasingly have to be able to go anywhere, and the way users experience it will be even more nonlinear than what it already is today.

We’re all well accustomed to touch being an input method. With voice input on the rise, we are starting to take a more natural approach to the ways we interact with technology. For product design teams this means that we have to think beyond touch and the mouse as a way for users to interact with the products and services that we work on. Though we’re far from Underkoffler’s vision, we are increasingly seeing apps that can talk to each other—something that, with the user’s permission, will enable us to deliver more value and take away the user frustration of having to repeat information between product and service providers. For designers, however, it means that we increasingly need to consider other apps and systems as players as well as providing input to our product experiences.

Multidevice Design

Consider Cliff Kuang’s assertion that “If you want to imagine how the world will look in just a few years, […] skip Silicon Valley. Go to Disney World.”23 In this magical wristband world, the restaurants we visit will know we’re on our way before we’ve stepped into their venue. They’ll know our names, where we’ve been, where we’re going next, what we like, and they’ll adapt the service we receive accordingly.

It’s a much more scaled-back future than the one Underkoffler talks of, but it’s one where everything is connected. While we’re still some way away from it being everyday life, it reflects the development we’re seeing in both user expectations and technology trends around our multidevice experiences.

Increasingly, when it comes to thinking through and designing multidevice experiences, it’s not going to be as much about what the user does as it is about preempting what the user wants to do so that we can deliver the right content to the right device, at the right time. According to a Google study, 90% of users switch devices multiple times a day. With the growing number of devices that we use on a daily basis, users are expecting to be able to continue where they left off, irrespective of the device they are using. This means being able to do not only the same thing and have access to the same functionality, but also see the same content.

What this means for product design

A few years back, a big debate arose online on bespoke mobile websites versus responsive websites. Back then, the prejudice around what users do and don’t do on smartphones in particular, but also on tablets, was more prevalent than it is today, and part of the industry was arguing for cut-down versions of mobile experiences as a result. There will always be differences between devices, from the role they play to which device users prefer to use for certain things, as well as what’s a more optimal experience on one type compared to another. Today, however, it’s more widely accepted that users carry out more or less the same tasks, particularly on smartphones, as they do on laptops, though not necessarily in the same way.

For everyone involved in product design, this means that the starting point should always be to provide an equal experience on all devices so people’s interactions with them are similar (i.e., laptops, tablets, and smartphones). But we also need to look at the context of use and the strength/weakness of each type of device and adjust the what and then how accordingly. As we’ll cover further on in this book, devices also play a role in the experiences that we design, and defining that role is an important factor to consider.

Machine Learning and AI

Film and literature are filled with examples of AI, both the good and the bad. One of the most famous AI movies is 2001: A Space Odyssey, in which the spaceship’s sentient computer, a HAL 9000, is the most reliable computer there is, at least according to itself. It controls most of the spaceship’s (called Discovery One) operations, but soon starts killing off the crew. A less terrifying but still thought-provoking movie is Ex Machina, in which the protagonist Caleb, a programmer, wins a visit to his CEO Nathan’s home. Nathan asks him to look into whether Nathan’s humanoid robot Ava is capable of thought and consciousness as well as if Caleb is able to relate to her even though she’s artificial. It’s a captivating movie about the potential challenges we’ll have in the future around controlling AI as it becomes more sophisticated, as well as what it would do if it is set free. Though we are still some way from either of these scenarios becoming a reality, machine learning and AI are increasingly part of the products that we design.

What this means for product design

Taking advantage of machine learning and AI doesn’t have to go all out, but can include small integrations to provide an uplift to the product experience for users and the bottom line for the business. Examples include recommendations (sorting the data we have and prioritizing it so it adds more value and relevance to the user), predictions (looking at what’s next based on what you’re doing now), classifications (organizing things based on classes or categories), and clustering (looking at unsupervised categories and getting the machine to figure out how the things are organized).24

When it comes to implementing machine learning and AI, business requirements and goals will always be pushed. For example, as we’ve seen from former employees of Facebook, hard conversations increasingly need to be had around the use of data capture and interaction patterns. Those of us involved in product design that uses any kind of data to influence the product experience must be prepared to question and push back, if what’s asked by the business is not in the best interest of users. We all have a responsibility to make sure that we’re not creating a dystopian future in which the machines take over, and silently kill us off while they still consider themselves the most reliable “computers” there are, just like HAL.

Though this is a very pessimistic look at machine learning and AI, it is important to remember that AI and machine learning needs to be taught everything. What we put in impacts the end result, and if we put in biased or narrow data, then that is the world that the machine will evolve in. That becomes apparent in what we’ll cover nex: bots and conversational interfaces.

Bots and Conversational Interfaces

As the previous section covers, many movies feature AI. Some movies have even given rise to real-life AIs and bots:, for example, Iron Man’s Jarvis is the inspiration for Mark Zuckerberg’s personal smart home with the same name.

In 2017, talk of bots and conversational interfaces was everywhere. It was looked at as the next big thing, and briefs for bots as part of interfaces were appearing everywhere. Then the chat around bots got a little quieter. Even if bots didn’t live up to the hype, partly because of bad implementations, in some cases bots may offer real value—not only to the business, but also to the customer. Customer service is one such area.

The average customer service response time is 20 minutes, yet studies show that if that response time is cut to less than 3 or 4 minutes, a fivefold increase occurs in customer spending.25 But the use of bots and chat is not just for improving conversions. It’s a very appropriate medium when there are barriers to talking to other real people (e.g., picking up the phone in the work place).

What this means for product design

While a chatbot might seem like a straightforward “feature” to add, it comes with many considerations. It may be novel, but using chat is not always the best way for users to navigate their way around a product or service. When to use a bot should always be viewed in light of the context of the rest of the product and that of its users. And as we covered in the previous section, the machine learning and AI that powers it needs to be taught how to behave and respond, as well as how not to behave and respond in certain situations.

Additional considerations should be taken in how the bot is personified, if it is. What might be appealing to some might feel whimsical or too formal to others. Based on the role of the bot, finding the right balance between how it talks and behaves and how it looks is often critical to its success.

Voice UI

Though we are a long way away from the situation we see in the movie Her, voice has become more mainstream over the last couple of years. Millions of homes worldwide now have Alexa, Cortana, or Google Home present. By 2020, it’s estimated that 30% of all web browsing sessions will be carried out without a screen.26

While designing VUIs is new to most, it’s a kind of interaction that’s very natural for people. Just think of how we’d ask the questions in Google compared to how we would if we spoke to a person. Conversations are natural for us, though there is some first-use awkwardness to get past when it comes to VUIs. Most of us will speak in a somewhat oversimplified manner, slower and clearer than we normally do, to increase our chances of receiving an accurate answer.

The frustrations VUIs can cause when they don’t work (i.e., misunderstand you, hear you inaccurately, or do something different than what you asked), should not be taken too lightly, and the context of use is incredibly important for VUIs.

What this means for product design

Even if more devices on the market now, like Amazon Echo Show and the Google Home hub, provide visual results as well as spoken ones, when it comes to VUIs, there is less room for the product design team to provide multiple results to the user. As UX and product designers, we have to think of intuitive ways to deliver results that encourage a natural follow-up answer by the user. And we have to think about all the possible answers and questions the VUI will be subject to, and what to respond for each. While many UX designers have previously been able to “get away with” not accounting for every possible outcome or scenario and focus on the ideal and a couple of alternatives, VUIs require work that’s a lot more detailed. All the possible outcomes need to be identified and accounted for, and even if there is no result for a user’s query, there still needs to be an answer.

This brings up a different skill that’s also needed by the UX designer. There won’t always be a specific VUI copywriting team in place, and the role of writing out the initial VUI will often land on the VUI/UX designer.

IoT and the Smart Home

Disney released the movie Smart Home back in 1999. In it, an ever-present AI called PAT takes care of all your needs, from displaying menus on wall displays in the kitchen, to controlling the lights and the temperature in the house, to absorbing spilled milk on the floor and preparing food. Since then, numerous other movies have featured smart home aspects. There’s Stark Mansion in Iron Man with, among other things, see-through screens that cover the windows, displaying the weather and other essential information when you wake up. Then we have Nathan’s lab in Ex Machina with smart lighting. The movie Her features, besides the iMac-style laptop, a very apparent lack of screens in the apartment of the main character, Theodore Twombly. Everything is controlled through voice interactions and gestures, including when he plays a VR/AR game that is projected over his furniture.

Though there is a very close connection between AI-based voice assistants and the smart home, there is more to it than that. Many of us will start with a smart home speaker that lets us control music, set a timer, perhaps turn on and off the lights. Or by simply having smart meters, thermostats, and fire alarms. Though many of us are still skeptical about letting technology take over our homes, 68% of Americans are confident that smart homes will be just as commonplace as smartphones within 10 years.27 My prediction is that it will happen a lot quicker than that, but we have some hurdles to overcome before that happens.

We’re at a turning point; we’re sharing more and more data with the devices and technology services that we use. With the smart home, we’re going to be able to track everything, from what we do, to various aspects of the house itself. There’s a great deal of opportunity here for delivering value and easing everyday life, from being able to check whether the front door is locked and the stove turned off from afar, to automatically ordering food when our smart fridge notices that we’re out of groceries. But all of it involves data. We need to ensure that we not only gain users’ trust in how we handle this data—and of course, actually handle the data securely and ethically—but also avoid bombarding them with it and all the potentially accompanying notifications that could follow.

For the smart home to be adopted and become mainstream, we need to provide value, be reliable, and make the experience effortless. And there’s a great likelihood that we will do just that. Inherent in IoT and its definition is that it’s a network of objects that can communicate with each other by sending and receiving data, without the involvement of humans. Many of you who read this will be technology enthusiasts and early adopters, just like myself. But all new technology faces some resistance after the initial excitement wears off, just as there was back when Thomas Edison invented the electric lightbulb. At first people marveled at his creation when it started to light up the streets of New York in 1880, but later they started to mistrust the electric light and considered it unsafe for their homes when stories started to spread of horses being electrocuted from traveling over lanes where transmission cables had been laid.

What this means for product design

While severe accidents like that are not likely to happen, nor the skepticism to be as profound, the value in IoT, smart homes, and increasingly connected experiences across all of our devices lies in the data that we’ll share with technology, and technology providers, as well as between different touch points, like apps and operating systems. The aim should be to create devices and experiences that work seamlessly together, regardless of the kind or brand of device. This is where the true potential lies in connected experiences, and it’s not too far from what Underkoffler is talking about.

But until we reach that point, and in preparation of the same, there is plenty we can do to ensure that the experiences we design tell the right story, to the right user, at the right time, and on the right device. And there is plenty that we, the people behind these products and services, should do, in the best interest of everyone. In addition to taking an ethical approach overall, handling data, and not spamming users with notifications, we must also consider how our products and services can be misused, even if that is never the intention. As John Naughton, an author and professor of public understanding of technology at The Open University, writes: “The newest conveniences are now also being used as a means for harassment, monitoring, revenge and control.”28

AR and VR

In the movie Ready Player One, which is based on the novel of the same name, much of humanity uses virtual reality to escape the grim surroundings of the real world, or as the main character, Wade Watts, puts it: “there’s nowhere left to go, except the OASIS.” In the OASIS, which is the name of the VR software, people can be whoever they want to be; the only limit is your imagination. The movie takes place in Columbus, Ohio, in 2045 and is a fascinating, yet somewhat chilling, example of how we’re able to create worlds online that draw us in and away from the “real” world.

AR, however, has the ability to bridge this gap. According to a study carried out by Latitude, a Boston-based research firm, the real world is also increasingly becoming a platform: 52% of respondents said that they consider it another platform, where they expect the likes of 3D technology and AR to link the digital and physical.29 Though the hype around Pokemon Go died down not too long after it started, for many this was the first time they got to experience the “overlay” added to the world, where character and additional information was shown.

What this means for product design

Designing for VR and AR draws a lot from film and game design. As product designers, we need to evolve our skills beyond traditional product design as factors like depth, touch, sound, and emotion are all integral parts to the experience. There are additional considerations to keep in mind, such as that the player or user will assume that any object that is made part of the experience will have a role to play and an action or event associated with it, similar to the case with movies.

One of the biggest differences in designing for AR and VR is that the player or user is not just a passive observer but an actual part of the product experience story. Additionally, you’re designing for an immersive, 360° space rather than a fixed desktop, tablet, or mobile screen. There are a lot of specifics to keep in mind when it comes to AR and VR. To really understand what we’re designing for, we need to immerse ourselves in both VR and AR and experience it first hand.

Omnichannel Experiences

In a well-told story, everything from big to small details comes together. Today, we’re seeing how online and offline experiences are increasingly merging and influencing one another. For a few years now, we’ve been talking about omnichannel experiences. Omnichannel experiences are defined as cross-channel experiences, which include channels like social media, physical locations, ecommerce, mobile apps, desktops, and more. All of these channels are increasingly providing input and output for each other. Just as companies that optimized their mobile experience had an advantage a few years ago over those that didn’t, today companies that optimize so that the user can move seamlessly across channels will have a competitive advantage over those that don’t. Advantages will include higher conversion and increased brand loyalty as ease and equal experiences become ever more important.30

What this means for product design

The line between digital and physical environments is increasingly blurring. As they essentially become one and the same, product design teams will have to learn, relearn, and learn again to keep up with the changes in technology. This also means that everything is increasingly an experience and that team members beyond those with “UX” in their titles will benefit from at least a basic understanding of user experience design.

As for the actual UX designers, they will have to understand the digital aspect, device, and hardware capabilities, how the products they work on live outside the screen, the role and influence of context, and also the possibilities these provide.

Changes in Consumer Expectations

There are also changes in consumer expectations connected to the ways storytelling and product design are changing. Next we’ll look at three such areas that span both storytelling and product design.

Immediacy and tap-of-a-button expectations

One of the main impacts of the iPhone when it first came out, and all smartphones thereafter, has been a shift in user expectations. Everything is now available at our fingertips by reaching into our bags and pockets. We can hardly remember what is was like when we had to plan in advance or even go to the library to get answers. Instead we’ve come to expect an answer the moment we want to go somewhere, do something, or buy something.31

This immediacy is an increasing expectation from users and customers, from health providers that offer appointments 24/7, the tap-of-a-button expectations, to brands and governments being expected to respond and address matters on social media the minute they happen, and be transparent about it.

What this means for product design

What users have gotten used to in social media, they start to expect elsewhere for the products and services that they use. It’s increasingly important for brands and companies to know how to act and respond. With more bots and AI-driven interfaces, knowing when to hand off to a human being is crucial or it can have a negative impact on a brand and business.32

The “right here and now” immediacy also places an interesting aspect on content and context. As we’ll cover shortly, there is a growing expectation around “for me” and a growing emphasis on search as a shortcut straight into the most relevant thing that users are looking for. For anyone involved in product design, it means that we should be able to deliver our lines—that is, our content—in the blink of an eye, no matter where the user has come from.

Personalization and Tailored Experiences

An Ericsson Trend report captured personalization well: “Today you have to know all the devices. But tomorrow all the devices will have to know you.”33 The more we can tell about our users, and the more sophisticated machine learning and programmatic anything will become, the more tailored all our experiences will be. There will no longer be “one website” or one experience, but just as the results in our Google searches are already tailored to us specifically based on our previous searches and online behavior, so will all of our online experiences be.

What this means for product design

Personalization and tailored experiences don’t just have to do with content. There is a big opportunity in adapting users’ actual needs (e.g., larger or smaller font sizes, location, history, actions they’ve taken or not taken). To truly do so, however, we really need to understand their needs in the different contexts and situations they are in, and responsibly leverage the power of data.

Use of Search and How We Access Information

Many of us, myself included, have stopped memorizing certain things, like phone numbers—even our partner’s. Instead, we memorize where we can find that information. We’re becoming experts at searching, but even more so, we’re expecting to be able to find almost anything by searching, and our expectations of what we will find are growing.

Over the past year, Google in particular has reported about searches using the qualifiers “the best” and “should I.” This shows a shift in both trust and expectation. Users are increasingly turning to search in an advisory way, just as you would a friend. They’re asking for specific things, for them, and they expect a relevant answer.

In addition to this, users are increasingly using search as a way to navigate websites and apps, skipping the main navigation and jumping straight in. It’s at times quicker, and if the result they get back is any good, they get just what they need in that moment.

What this means for product design

When we define and design the pages/views and the overall experience of the products and services we work on, we increasingly need to do that with a key consideration in mind: users will most likely not arrive on the home page first. In fact, the “home page” of our products or services is often search.

This has implications for the way we think about content and page design. The background context that users otherwise would have gotten if they’d navigated through our website or app in the way we usually so carefully plan it out is often not there. Instead, a user should be able to grasp that context, or at least part of it, regardless of what page they first land on.

Summary

Over the years, storytelling has influenced and driven innovation in both science and technology, from Sherlock Holmes and how crimes are solved, to Star Trek providing inspiration for Amazon’s Alexa. Storytelling has also played a critical part in communication and connecting with audiences, and that’s something we’re increasingly struggling to do with the products and services that we’re working on today.

The context in which they are used is becoming more complex by the day. At the same time, users are increasingly expecting products and services to work for them, specifically, no matter where they are, what device and input methods they are using, and in whichever way they want to use them.

Designers require new skills, as what we’re designing increasingly involves AI and machine learning, multiple touch points, connected devices and apps, as well as a mixture of interfaces we touch, interfaces we talk to, interfaces we cannot see, and those that we are an actual part of through sensory data or AR and VR. As designers, we need to master Walt Disney’s skill of being be able to get the bigger picture right in addition to the small details. We also need to account for a growing number of eventualities and moving parts that need to be defined and designed, so that they all come together. Just like a good story.

1 Lynsey Barber Barber, “We’re Spending Billions Shopping Online While Commuting,” City A.M., July 2, 2015, https://oreil.ly/MieZG.

2 Amy Watson, “Subscription Video On Demand,” Statista, October 10, 2018, https://oreil.ly/RB51N.

3 Amy Watson, “E-books - Statistics & Facts,” Statista, December 18, 2018, https://oreil.ly/wDqhe.

4 Sirena Bergman, “We Spend a Billion Hours a Day on YouTube, More Than Netflix and Facebook Video Combined,” Forbes, February 28, 2017, https://oreil.ly/UsdVP.

5 Caitlin O’Kane, “The 10 Highest-Paid YouTube Stars of 2018, According to Forbes,” CBS News, December 4, 2018, https://oreil.ly/qrYup.

6 Lance Weiler, “How Storytelling Has Changed in the Digital Age,” World Economic Forum, January 23, 2015, https://oreil.ly/oTAuD.

7 Kelly Song, “Virtual Reality and Van Gogh Collide,” CNBC, September 24, 2017, https://oreil.ly/QPGIK.

8 “The Night Cafe: A VR Tribute to Van Gogh,” Oculus, https://oreil.ly/n_hkO.

9 What Is Immersive Storytelling?” The CMO Show, https://oreil.ly/ZTcKl.

10 Scott Meslow, “Are Choose-Your-Own-Adventure Movies Finally About to Become a Thing?” GQ, June 21, 2017, https://oreil.ly/kCgT5.

11 Owen Gibson, “What Happens Next?” The Guardian, September 26, 2005, https://oreil.ly/qCNtj.

12 PSFK Originals, “Participatory Storytelling in Advertising,” YouTube Video, March 22, 2013, https://oreil.ly/r-Qh6.

13 Kristin Westcott Grant, “Netflix’s Data-Driven Strategy Strengthens Claim for ‘Best Original Content’ in 2018,” Forbes, May 28, 2018, https://oreil.ly/YhqCW.

14 Sebastian Wernicke, “How to Use Data to Make a Hit TV Show,” TEDxCambridge Video, June 2015, https://oreil.ly/S9ME2.

15 Lance Weiler, “How Storytelling Has Changed in the Digital Age,” World Economic Forum, January 23, 2015, https://oreil.ly/R6MFc.

16 “Transmedia Storytelling,” BBC Academy, September 19, 2017, https://oreil.ly/GsblO.

17 Kayti Burt, “What Is Skam and Why Is It Taking Over the Internet?” Den of Geek, April 9, 2017, https://oreil.ly/9c0CE.

18 KC Ifeanyi, “The Future of Storytelling,” Fast Company, August 17, 2012, https://oreil.ly/baLgf.

20 Bryant Urstadt and Sarah Frier, “Welcome to Zuckerworld,” Bloomberg Businessweek, July 27, 2016, https://oreil.ly/qOgRU.

21 Lisa Gevelber, “It’s All About ‘Me’,” Think with Google, January 2018, https://oreil.ly/SIw3m.

22 Zoe Mutter, “Why We Need Critical Dialogue Around the User Interface,” AV Magazine, November 2, 2018, https://oreil.ly/p0WKB.

23 Cliff Kuang, “Disney’s $1 Billion Bet on a Magical Wristband,” Wired, March 18, 2015, https://oreil.ly/SzDnI.

24 Josh Clark, “The New Design Material,” beyond tellerrand, November 5, 2018, https://oreil.ly/AoyK-.

25 Eleanor Kahn, “Bots Are Still in their Infancy,” Campaign, June 21, 2017, https://oreil.ly/QEMpA.

26 Raffaela Rein, “UX Design Trends for 2018,” Invision, January 4, 2018, https://oreil.ly/_LIne.

27 Chris Klein, “2016 Predictions for IoT and Smart Homes,” The Next Web, December 23, 2015, https://oreil.ly/rljG8.

28 John Naughton, “The Internet of Things Has Opened Up a New Frontier of Domestic Abuse,” The Guardian, July 1, 2018., https://oreil.ly/pksjf.

30 Kim Flaherty, “Seamlessness in the Omnichannel User Experience,” Nielsen Norman Group, March 19, 2017, https://oreil.ly/YWIrz.

31 Natalie Zmuda, “The New Customer Behaviors That Defined Google’s Year in Search,” Think with Google, December 2017, https://oreil.ly/yrUsK; Lisa Gevelbier, “Micro-Moments Now,” Think with Google, July2017, https://oreil.ly/vAshk.

32 The State of UX in 2019, https://trends.uxdesign.cc/.

33 “10 Hot Consumer Trends 2018,” ericsson.com, https://oreil.ly/N6B9v.